The history of Budapest, as the heart of Hungary, is intrinsically linked to the evolution of its currency. Since medieval times, the region we know today as Budapest has been a centre of power and economic activity, which naturally made it a focal point for the minting of coins and the development of monetary systems in the country. Historical records mention the existence of forints minted under the reigns of Louis I of Hungary (1342-1382) and Matthias Corvinus (1458-1490), figures whose courts and governments had a significant influence in shaping modern Hungary, with Buda as a major centre.

The Hungarian monetary system underwent a radical transformation after World War II. The massive hyperinflation of the pengő in 1945-46, considered the highest ever recorded, devastated the country’s economy. In response to this crisis, the Hungarian forint was introduced on 1 August 1946 as a crucial measure to stabilise the economy. The reintroduction of the forint on this date, with a theoretical exchange rate of 1 forint to 4×1029 pengő, marked a new beginning for the Hungarian economy, leaving behind a period of unprecedented financial chaos. The choice of the name ‘forint’, with its historical roots in gold coins dating back to the 14th century. This change of currency was not simply an administrative reform, but a fundamental step to restore economic order and public confidence after a period of instability.

Coins in Circulation

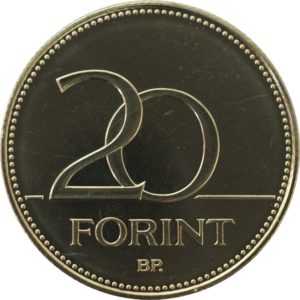

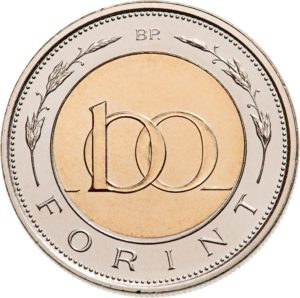

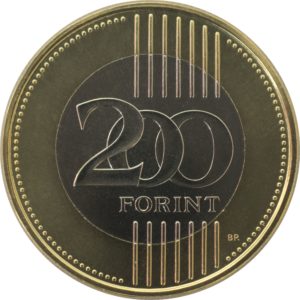

Hungary currently has six denominations of coins in circulation: 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 forints. Each of these coins is distinguished by its materials, design and symbols representing the Hungarian identity.

- 5 forint coin is made of a copper alloy (Cu75Ni4Zn21), has a yellow-golden colour and a smooth edge. Its design features the image of a Great Egret (Egretta alba).

- 10 forint coin, made of a copper alloy (Cu75Ni25), is silver in colour and has a milled edge (70) with smooth sections. Its design shows the coat of arms of Hungary.

- 20 forint coin, similar to the 5 forint coin in its composition (Cu75Ni4Zn21) and yellow gold colour, has a milled edge (130) and features the Hungarian Iris (Iris aphylla hungarica).

- 50 forint coin, made of copper alloy (Cu75Ni25), is silver-plated, has a smooth edge and bears the image of the Saker Falcon (Falco cherrug).

- 100 forint coin is bi-metallic. Originally made of coated steel (silver-plated ring, gold core), since October 2019 it is also minted with a copper alloy (silver-plated ring: Cu65Ni15Zn20, gold core: Cu75Ni4Zn21), keeping the same design of the Hungarian Coat of Arms and a milled edge (170). Both versions are currently in circulation.

- 200 forint coin is also bi-metallic (gold ring: Cu75Ni4Zn21, silver core: Cu75Ni25) with a milled edge (72) with smooth sections, and its iconic design shows the Chain Bridge in Budapest.

Banknotes in circulation

There are six denominations of banknotes in circulation in Hungary: 500, 1,000, 2,000, 5,000, 10,000 and 20,000 forints. Each banknote features a portrait of a major Hungarian historical figure on the front and a significant monument or scene related to that figure on the back.

- 500 forint banknote shows the portrait of Prince Ferenc II Rákóczi and the reverse depicts Sárospatak Castle.

- 1,000 forint banknote bears the image of King Matthias Corvinus on the obverse and the Fountain of Hercules in Visegrád on the reverse.

- 2,000 forint banknote features Prince Gábor Bethlen on the obverse and a scene of him among his scientists on the reverse.

- 5,000 forint banknote honours Count István Széchenyi on the obverse and shows his mansion in Nagycenk on the reverse.

- 10,000 forint banknote features the portrait of King St. Stephen on the obverse and a view of Esztergom on the reverse.

- 20,000 forint banknote commemorates Ferenc Deák on the obverse and features the former Parliament Building in Pest (Budapest) on the reverse.

Historical Evolution and Cultural Context

The monetary system in Budapest has undergone numerous changes reflecting the political and social transformations in Hungary. During the Austro-Hungarian Empire, between 1868 and 1892, the forint was used, but was replaced by the krona, and later, in 1927, by the pengő. However, severe hyperinflation of the latter currency after World War II forced the country to reinstate the forint in 1946.

En la época comunista (1949-1989), el forint se mantuvo relativamente estable gracias al control centralizado de la economía. Sin embargo, con el paso del tiempo, su valor se fue debilitando. En 1968, el gobierno introdujo el Nuevo Mecanismo Económico, que incorporó ciertos elementos de mercado en el sistema planificado, lo cual contribuyó gradualmente a un aumento de la inflación. Ya en los años 90, al dar el paso hacia una economía de mercado, el país enfrentó nuevos retos, como una elevada inflación, que alcanzó su punto más alto en 1991.

Under communism, the emphasis on state planning sought price stability, but in the long run affected competitiveness and purchasing power. With the advent of the free market system in the 1990s, the country managed to modernise and integrate with the West, albeit with some initial economic instability.

Despite these ups and downs, the forint remains Hungary’s official currency, even after its accession to the European Union in 2004, without having yet adopted the euro. Moreover, forint banknotes and coins play an important role in building national identity: their designs depict historical heroes and emblematic monuments of Budapest, such as the Chain Bridge, helping to keep collective memory alive and reinforcing cultural pride from generation to generation.

Comments are closed.