The Rubik’s Cube is much more than a toy: it is a worldwide symbol of ingenuity, logic and perseverance. Since its creation in 1974, it has captivated millions of people thanks to its contrast between a simple appearance and impressive mathematical complexity, with more than 4.3 × 10¹⁹ possible combinations. As well as entertaining, it has established itself as an educational tool that stimulates spatial reasoning, memory and problem solving, and has spawned a global community of enthusiasts who share techniques, compete and celebrate their passion for this puzzle.

What many do not know is that the Rubik’s Cube has Hungarian roots: it was invented in Budapest by Ernő Rubik, a sculptor and professor of architecture, who initially called it the ‘Magic Cube’. The connection with the Hungarian capital goes beyond its origin, as Budapest also hosted the first edition of the World Rubik’s Cube Championship in 1982, cementing its role as the birthplace of this global phenomenon.

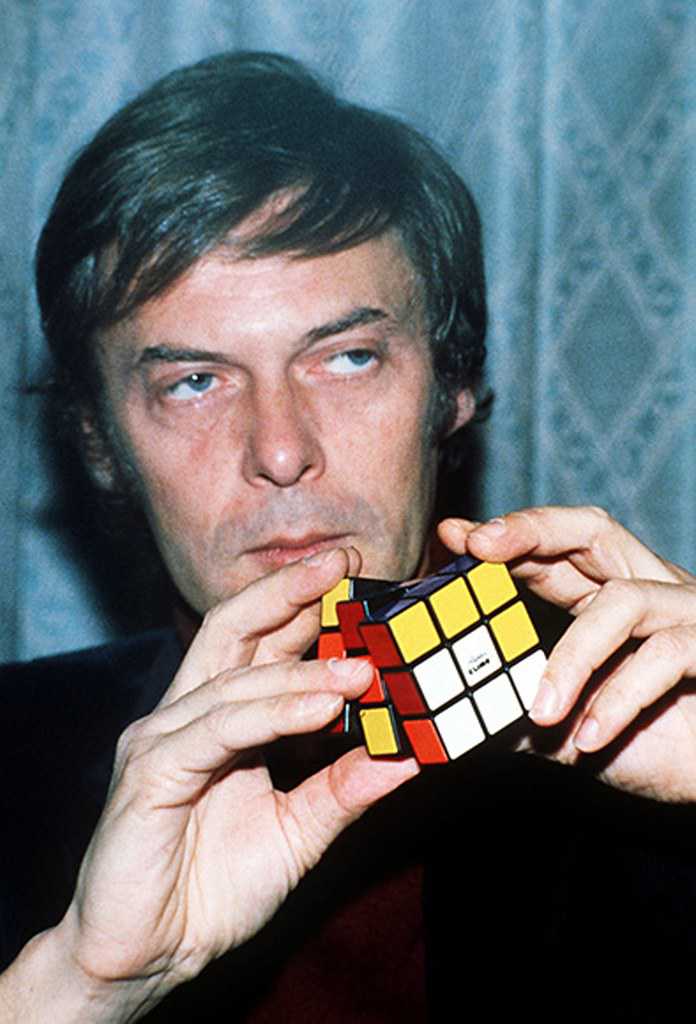

Who is Ernő Rubik?

Ernő Rubik was born on 13 July 1944 in Budapest, Hungary. He was born during the Second World War, in a Budapest hospital converted into an air-raid shelter. Throughout his life, Rubik has remained in his native country.

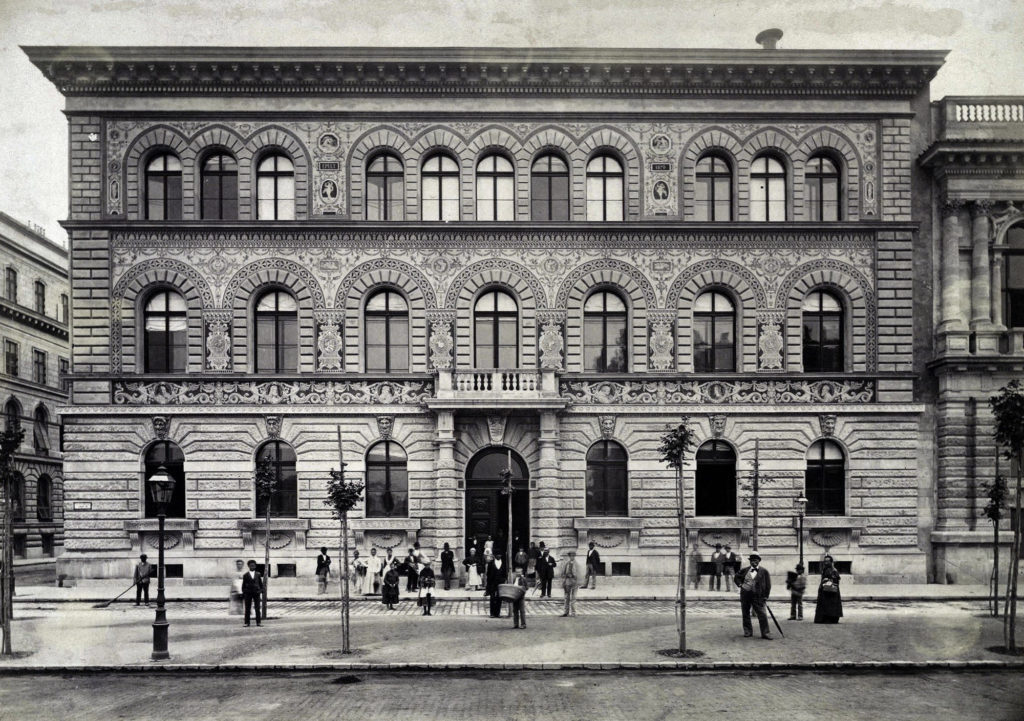

His academic training was remarkably diverse, encompassing sculpture, architecture, design and mathematics. He studied sculpture at the Technical University of Budapest and later turned to architecture at the Academy of Applied Arts and Design, also in Budapest, where he obtained his diploma in 1967. His interest extended to interior design, a field in which he also trained at the Hungarian Academy of Applied Arts and Crafts, obtaining a diploma in 1971. His penchant for geometry and the study of three-dimensional forms was also an important factor in his career.

After completing his training, Ernő Rubik worked as a lecturer at the Budapest Academy of Applied Arts (now the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design) from 1971 to 1979. During this time, he also worked as an architect from 1971 to 1975. His teaching was a direct catalyst for the invention of the cube. Looking for an effective tool to explain three-dimensional concepts to his students, he experimented with the idea of a cube with moving parts. His pedagogical approach was based on the use of physical models, made of various materials, to challenge his students to experiment with clearly constructed shapes. In 1987, he was appointed full professor.

The birth of the cube

The invention of the Rubik’s Cube arose directly from Ernő Rubik’s pedagogical need to find a teaching tool to explain three-dimensional geometry to his students. He was looking for a way to demonstrate movement in three-dimensional space and to give his students a portable object with which they could interact to better understand geometric shapes and spatial relationships. His initial goal was not to create a cultural phenomenon, but to build a large cube out of smaller cubes that could move without falling apart, thus facilitating the understanding of three-dimensionality for his architecture students. In addition to his educational purpose, Rubik had a deep personal fascination with geometry and the challenge of creating a functional structure with moving parts. He was especially intrigued by the structural problem of how to make the blocks move independently without the whole structure falling apart. In fact, he came to see the cube as a work of art, a moving sculpture symbolising the stark contrasts of the human condition. He later acknowledged that he also set out to design a puzzle based on geometric principles.

The first prototype of the Rubik’s Cube was built with simple materials: 27 small wooden blocks held together with rubber bands. Rubik chose wood for its ease of use and the availability of a workshop at the university. He created this prototype by hand, cutting the wood, drilling the holes, and using the rubber bands to hold it together. He also employed paper and paper clips in his initial experiments. His first attempts even included an unstable 2×2 puzzle. He experimented with rubber rings and magnets, but none of these solutions proved satisfactory, as the cube frequently fell apart. For months, Rubik spent time manipulating wooden and paper cubes, held together with rubber bands, glue, and paper clips. These humble materials of the first prototype reflect the initial focus on functionality rather than mass production. The process of trial and error, including less successful attempts, underscores the iterative nature of invention.

Rubik originally named his creation the “Magic Cube” (“Bűvös Kocka” in Hungarian). He applied for a patent in Hungary for his “Magic Cube” on January 30, 1975, which was granted that same year. He received the patent in 1977. The first test batches of the Magic Cube were produced in late 1977 and launched in toy stores in Budapest. In 1979, he licensed the “Magic Cube” to the American toy company Ideal Toys.

Budapest as context

Budapest in the 1970s, despite being under communist rule, was a dynamic academic and intellectual center, particularly in mathematics, science, and design. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Hungary experienced a period of educational reform under the Kadar regime, moving away from severe international isolation. This period witnessed intense development in educational policy, which arguably outpaced reforms in neighboring countries, contributing to the illusion of a “livable socialism.” Hungary joined the IEA (International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement).

There was a focus on developing methods for teaching mathematics, with significant projects such as the one led by Tamás Varga that sought a complete overhaul of methods and content. Mathematics teaching has always been highly valued in Hungary, ranking second in importance only to Hungarian language, literature, and history. The standard of mathematics teaching was considered quite high in Hungary due to ingenuity and a highly organized school system. The 1970s witnessed debates and reforms in mathematics education, including the introduction of functional thinking. Hungary has a tradition of producing highly talented mathematicians and physicists, with a strong emphasis on problem-solving in education. There were specialized mathematics secondary schools in Budapest, which fostered an environment focused on enrichment and creative problem-solving. The Budapest School of Applied Arts, where Rubik taught, underwent renovations in the 1960s and was elevated to university status in 1971, reflecting a growing appreciation for the applied arts. There was also a vibrant art and design scene in Budapest, influenced by movements such as the Bauhaus.

However, communist Hungary presented significant difficulties in marketing the cube outside the country. A communist command economy had been established, hindering the country’s development. Hungary was behind the Iron Curtain, an Eastern Bloc state controlled by communists until 1989. Communist-era Hungary’s strictly controlled exports complicated the continued growth of the Magic Cube. The country had no particular affinity for toy production at the time. Puzzles were sold primarily in souvenir and specialty shops, and considering them toys was a novel concept. Crossing the Iron Curtain to introduce the Cube to America was no easy task. Rubik was only allowed to purchase a small amount of cash, which was not enough to promote the Cube. Communist Hungary’s rigid planned economy initially made it difficult for Rubik to find a manufacturer. He eventually found a small company that made chess pieces. The journey from academic prototype to commercial puzzle was challenging, as Hungary was under state socialism and five-year economic planning, not exactly ideal for a new product like a puzzle. It took three years for the puzzle to go into production in Hungary. The first order in Hungary was for 5,000 units, and by 1980, one million had been sold there. The New Economic Mechanism in Hungary, although seeking reform, faced challenges and inconsistencies. The Hungarian economy in the late 1970s faced problems such as declining investment and rising foreign debt. Moscow’s trade demands on Hungary were tightening, demanding more exports and higher-quality goods.

From Budapest to the world

The Rubik’s Cube began its journey from Budapest to the world thanks to key individuals who recognized its potential. Entrepreneur Tibor Laczi took the Magic Cube to the Nuremberg Toy Fair in Germany in February 1979 with the goal of popularizing it. There, it was discovered by Tom Kremer, founder of Seven Towns Ltd., who firmly believed in its potential. Kremer negotiated a deal with Ideal Toys in September 1979 to launch the Magic Cube worldwide. The puzzle made its international debut at toy fairs in London, Paris, Nuremberg, and New York in January and February 1980.

In 1980, Ideal Toys made the strategic decision to rename the “Magic Cube” as the “Rubik’s Cube.” This move was intended to create a recognizable brand and facilitate trademark registration, directly associating the product with its inventor, Ernő Rubik. Other names, such as “The Gordian Knot” and “Inca Gold,” were considered, but the final choice was “Rubik’s Cube.” The first batch of cubes bearing the new name was exported from Hungary in May 1980.

Following its international launch, the Rubik’s Cube experienced unprecedented success, becoming an instant global phenomenon. Millions of people were captivated by the challenge of aligning its colorful squares, and speedcubing competitions quickly sprang up. In 1980, it won the special award for Best Puzzle of the Year in Germany, and garnered similar accolades in the United Kingdom, France, and the United States. By 1981, the Rubik’s Cube had become a bona fide fad, with an estimated 200 million units sold worldwide by 1983. The first speedcubing championship organized by the Guinness Book of World Records was held in Munich in March 1981. The cube appeared on the cover of Scientific American in March 1981, further cementing its status. It quickly became an icon of popular culture, with its colors adorning a wide range of products. It was featured in television commercials, newspaper advertisements, and even an animated series titled “Rubik the Amazing Cube.” Books on how to solve the cube became bestsellers.

Although the initial craze subsided, the Rubik’s Cube experienced a resurgence in the early 2000s, with a significant increase in sales. In 2004, the World Cube Association (WCA) was formed, which organizes worldwide competitions and recognizes world records. Annual sales reached millions of units in the following years. By January 2024, around 500 million cubes had been sold worldwide, making it the world’s best-selling puzzle game and toy. The current speedcubing record stands at under 4 seconds, with Max Park holding the record with an impressive time of 3.13 seconds. Speedcubing has established itself as a competitive sport with a dedicated global community.

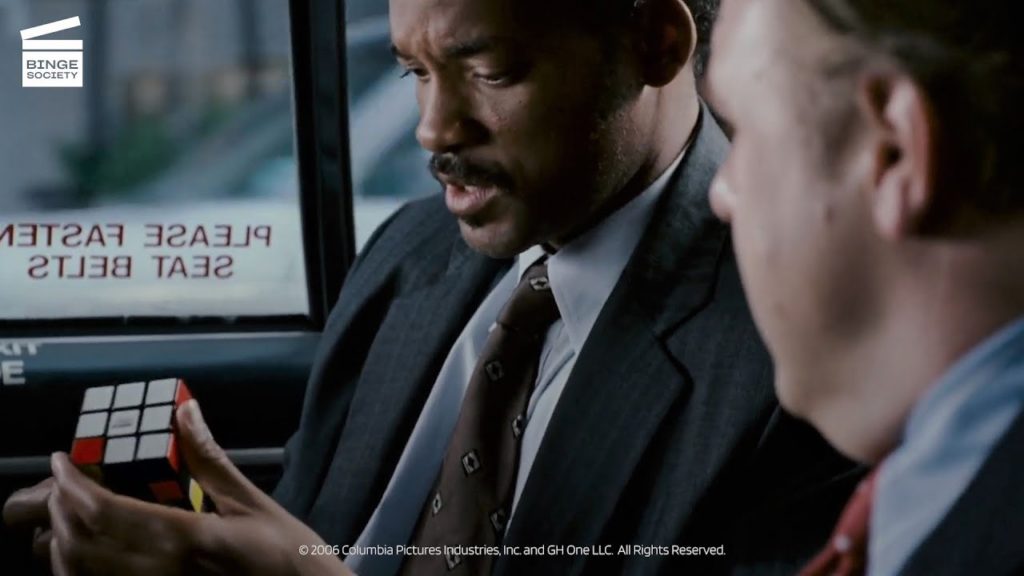

The Rubik’s Cube has left an indelible mark on culture, symbolizing problem-solving and ingenuity. It has appeared in numerous films and television shows (such as The Simpsons, The Big Bang Theory, Rick and Morty, The Pursuit of Happyness), music videos (Spice Girls, Genesis), and commercials. It has inspired various forms of art, including Rubik’s Cube art, mosaics, and sculptures. There is even a Rubik’s Cube sculpture in Budapest. It has also influenced architecture. In 2014, Google dedicated an interactive Doodle to its 40th anniversary. That same year, it was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame. It has been used as a metaphor for the complexities of life. Even medical conditions such as “cube thumb” or “Rubik’s wrist” have been associated with its use. Its creator considers it a work of art. An estimated one in seven people worldwide has played with a Rubik’s Cube.

Current legacy

Ernő Rubik has actively leveraged the popularity of his invention to promote education, particularly in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). He is involved with the Rubik Learning Initiative, which aims to spark young students’ interest in these areas and in problem-solving. At the Hungarian Academy of Engineering, of which he served as president in 1990, he established the International Rubik Foundation to support talented young engineers and industrial designers. There is an educational program called “You Can Do the Rubik’s Cube” that focuses on learning mathematics and 21st-century skills. The cube has become a tool for developing spatial reasoning and problem-solving skills. Schools have adopted it as an educational aid. It can be used to teach students algorithms. It has real-world applications in the field of STEM education. Solving it improves cognitive skills. It activates both hemispheres of the brain, making it an excellent mental exercise.

The Rubik’s Cube has exerted a significant influence on generations of engineers, mathematicians, and gamers. It has become a tool for developing spatial reasoning and problem-solving skills. It helps understand three-dimensional objects. It is used as a teaching tool in fields such as physics and group theory. It has inspired algorithms that contribute to diverse fields of research and problem-solving strategies. Its challenge is enjoyed by gamers and puzzle enthusiasts. It has spawned a subculture dedicated to competitive speedcubing. It has attracted young amateurs (“cubers”) skilled at pattern identification (algorithms). It helps improve mental flexibility. It activates parts of the brain responsible for problem-solving, spatial awareness, and memory. It improves problem-solving skills.

As for Ernő Rubik’s current activities, he will be 80 years old in 2024 and is still active. He lives between Budapest and Spain with his wife, with whom he has three daughters and a son. Much of his recent work focuses on promoting science in education. He is involved with organizations such as Beyond Rubik’s Cube, the Rubik Learning Initiative, and the Judit Polgar Foundation. He co-created the traveling science exhibition “Beyond Rubik’s Cube.” He still runs Rubik Studios, where he works on video game development and architectural themes. He founded the studio in 1983 to design furniture and games. In 2009, he became an honorary professor at Keimyung University in South Korea. He has given lectures and autograph sessions at various conferences. He is the co-author of books such as “The Magic Cube” and “The Rubik’s Cube Compendium,” and wrote “Cubed – The Puzzle of Us All.” At the Georgia Institute of Technology, he gave a public lecture discussing design, architecture, curiosity, and his perspective on the Rubik’s Cube. He participated in a special session celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Rubik’s Cube in January 2024 via video conference from Spain. He considers the Rubik’s Cube a work of art and hopes the cube will continue to thrive for at least another 50 years.

Comments are closed.