Budapest, the vibrant capital of Hungary, owes its existence to the 1873 unification of three distinct settlements: Buda, Pest, and Óbuda. This city, strategically located on the banks of the Danube, has served as a crucial crossroads of European history for centuries. Within this rich tapestry of historical development, the Jewish community has played an enduring and multifaceted role, leaving an indelible mark on the city’s identity, culture, and progress. From its earliest traces in Roman times to its vibrant presence today, the story of Jewish settlement in Budapest is one of resilience, contribution, and profound historical significance. This article aims to provide a concise yet comprehensive overview of this remarkable journey, highlighting the key periods, pivotal events, and lasting impact of the Jewish people on the life and character of Budapest.

The Origin and History of the Jewish Quarter

The Jewish presence in Budapest dates back to Roman times, with the first indications of a Jewish community emerging during the Roman Empire. In the 13th century, a significant influx of Jews occurred when King Béla IV invited them to settle in Hungary, granting them legal residence and religious autonomy. This migration was partly motivated by the desire to assist in rebuilding efforts following the devastation caused by the Mongol invasions.

During the medieval period, Jews in Budapest engaged in various occupations, including commerce, finance, and craftsmanship. The community faced periods of expulsion, notably in 1348 and 1360, but was generally allowed to return shortly after each expulsion. The 16th century brought significant change as the Ottoman Empire established control over Hungary. Sephardic Jews from regions like Istanbul, Salonica, and Belgrade began settling in Budapest, enriching the city’s Jewish cultural tapestry.

The 19th century marked a period of rapid growth for Budapest’s Jewish community. The unification of Buda, Pest, and Óbuda in 1873 created a metropolis where Jews constituted a substantial portion of the population. By 1869, approximately 45,000 Jews resided in Budapest, and this number surged to over 215,000 by the early 20th century, making up about a quarter of the city’s inhabitants. This demographic boom facilitated the construction of significant religious and cultural institutions, including the Grand Synagogue on Dohány Street, which remains the largest in Europe.

However, the interwar period and World War II brought profound challenges. Hungary’s alliance with Nazi Germany led to the implementation of oppressive laws and, eventually, the occupation of Hungary in 1944. During this time, Jews in Budapest were confined to “yellow-star houses” — designated buildings marked with a visible yellow star where approximately 220,000 Jews were forced to live before being deported to ghettos and concentration camps. Post-war, the community faced the arduous task of rebuilding amidst the broader backdrop of Soviet influence and communism.

Another somber memorial is the “Shoes on the Danube Bank,” a poignant monument that commemorates the Jews who were shot by fascist Arrow Cross militiamen in 1944. The victims were forced to remove their shoes before being executed, and their bodies fell into the river. The memorial consists of 60 pairs of rusted shoes placed along the Danube, symbolizing the diverse individuals, including men, women, and children, who perished in this horrific act.

The Communist era saw the Jewish community continue to evolve under restrictive political conditions. Religious and cultural practices were suppressed, and many Jewish institutions faced limitations. However, following the fall of communism in the late 1980s, the Jewish Quarter began to experience a renaissance, marked by the restoration of historic buildings, the revival of cultural and religious life, and the flourishing of a vibrant modern-day Jewish community. Today, Budapest’s Jewish community stands as a testament to resilience and cultural richness, with its history intricately woven into the broader narrative of the city’s development.

Synagogues and Historical Monuments

The Great Synagogue of Budapest (Dohány Street Synagogue)

The Dohány Street Synagogue, often referred to as the Great Synagogue, stands as the largest synagogue in Europe and the second largest globally. Located in Budapest’s historic Jewish quarter, it was constructed between 1854 and 1859 in the Moorish Revival and Romantic Historicist styles. Designed by architect Ludwig Förster, the synagogue features twin octagonal towers and onion domes, reflecting a blend of architectural influences. Its capacity to seat approximately 3,000 worshippers underscores the prominence of Budapest’s Jewish community during the 19th century.

The synagogue’s design is a fusion of various architectural styles, including Moorish, Byzantine, Romanesque, and Gothic elements. The façade is adorned with alternating yellow and red brickwork, and the interior boasts a spacious central nave flanked by two balconies, supported by a single-span cast iron structure. The richly decorated Torah ark and the presence of a pipe organ are notable features. Beyond its architectural grandeur, the synagogue serves as a central hub for Neolog Judaism, offering regular worship services, cultural events, and educational programs that cater to both the local and international Jewish communities.

Adjoining the synagogue is the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives, established in 1930. The museum houses a vast collection of religious artifacts, including ritual objects used during Shabbat and major Jewish holidays, as well as items from the Holocaust era. The museum’s proximity to the synagogue highlights the intertwined nature of worship and cultural preservation within the Jewish community. It provides visitors with a comprehensive understanding of the history, traditions, and contributions of Hungarian Jewry, making it an integral part of the synagogue complex.

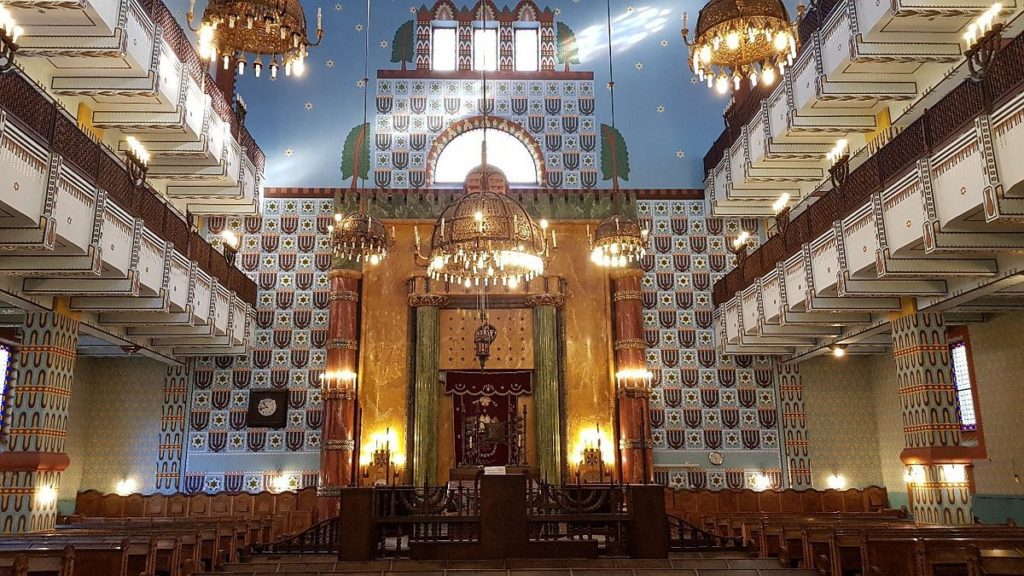

The Kazinczy Street Synagogue

Nestled in the heart of Budapest’s historic Jewish Quarter, the Kazinczy Street Synagogue may be modest in size compared to its grander counterpart on Dohány Street, but it carries a wealth of history and cultural significance. Constructed in the early 20th century, this synagogue reflects a simpler architectural style that emphasizes functionality and community spirit. Its unassuming façade and intimate interior design are a testament to the resourcefulness and resilience of the local Jewish community during times of both prosperity and hardship.

Over the decades, the Kazinczy Street Synagogue has served not only as a place of worship but also as a vibrant center for community gatherings and cultural events. It has played an integral role in nurturing the communal identity of Budapest’s Jews, hosting religious ceremonies, educational programs, and cultural festivities that celebrate Jewish heritage. Today, it stands as a living monument to the enduring legacy of the neighborhood, reminding locals and visitors alike of the deep-rooted traditions and communal bonds that continue to define the area.

The Jewish Cemetery

During World War II, discriminatory policies and the horrors of the Nazi occupation forced the marginalization of Budapest’s Jewish community to an extreme. Many Jews were denied burial in conventional cemeteries due to anti-Semitic laws and widespread prejudice. As a result, a separate Jewish Cemetery was established, serving as the only resting place for those who were systematically excluded from traditional burial grounds. This cemetery stands as a stark reminder of the brutal reality faced by the community, where countless individuals were left without a dignified resting place during one of history’s darkest chapters.

In the years following the war, the cemetery evolved into a vital memorial, preserving the memory of those who suffered immeasurably during the Holocaust. It not only commemorates the lives of those who could not be interred elsewhere but also serves as a powerful symbol of resilience and remembrance for future generations. Visitors and community members come to the site to reflect on the past, honor the legacy of their ancestors, and reaffirm the commitment to ensuring that the tragedies of the past are neither forgotten nor repeated.

The Tree of Life

The Holocaust Memorial Monument in the garden of the Great Synagogue is a moving tribute to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, inviting reflection and honoring the lives lost during World War II. The monument is thoughtfully designed to integrate into the synagogue’s sacred garden, making it a place for solemn contemplation and prayer. It serves not only as a historical marker but as a spiritual space, emphasizing the importance of remembering the atrocities committed and the resilience of the Jewish community.

At the heart of the memorial is the Tree of Life (“Etz Chaim”), a significant symbol in Judaism representing the Torah, wisdom, and the connection to God. In this context, the tree stands for resilience, hope, and the continuity of life despite immense loss. Its presence in the memorial symbolizes the strength of the Jewish community during and after the Holocaust, a reminder that faith and culture endured despite the destruction.

The Tree of Life also symbolizes the resistance and hope that sustained the Jewish people throughout the Holocaust. Its branches and leaves represent the sorrow of the past and the enduring strength of survivors, signifying the rebirth and renewal of the Jewish community. This powerful metaphor creates a profound connection between historical memory and the ongoing resilience of the Jewish people, offering visitors an opportunity to reflect on both the tragedy and the survival that followed.

The memorial is further personalized through the engraved names on the metal leaves of the sculpture. These leaves bear the surnames and registration numbers of Holocaust victims from Hungary, emphasizing the human cost of the tragedy. By transforming the vast number of victims into individuals with identities and families, the memorial fosters a deeper emotional connection for visitors, highlighting the personal impact of the Holocaust and ensuring that the victims are remembered as real people, not just statistics.

The Vibrant Culture of the Jewish Quarter

The Jewish Quarter’s transformation has also been fueled by grassroots initiatives and local entrepreneurs who saw potential in its forgotten courtyards and historical façades. Rather than opting for full-scale modernization, many have embraced adaptive reuse, turning decaying buildings into vibrant cultural venues that preserve the neighborhood’s soul. This thoughtful approach has helped maintain the area’s authenticity, drawing visitors not only for its aesthetics but also for its atmosphere of creative reinvention and cultural depth.

The presence of young creatives has led to a fluid cultural dialogue where contemporary ideas naturally integrate with heritage. Cafés double as co-working spaces and event venues, while old kosher bakeries sit next to fusion food joints and minimalist concept stores. It’s common to see mezuzahs on doorframes near colorful murals or hear klezmer music during cultural events next to experimental electronic performances. This fusion of old and new gives the neighborhood a rhythm that is distinctly Budapestian—anchored in memory but always evolving.

Ruin Bars: The Alternative Soul of the Neighborhood

The Origin of Ruin Bars

Ruin bars began as a creative solution to a post-communist urban problem: Budapest’s inner districts were full of neglected buildings and crumbling courtyards. In the early 2000s, a group of young locals saw opportunity in this decay and transformed one such abandoned space into a laid-back, makeshift bar. The concept quickly gained momentum, offering an affordable and edgy alternative to mainstream nightlife. Rather than renovating, the idea was to work with the existing ruins—leaving peeling walls, exposed pipes, and mismatched furniture as part of the aesthetic.

What makes ruin bars so captivating is their contrast: decaying, often century-old buildings filled with bursts of life, string lights, quirky installations, graffiti, and an eclectic mix of vintage and DIY decor. These spaces feel more like community art projects than commercial venues. The atmosphere is relaxed, inclusive, and spontaneous, attracting creatives, musicians, and curious travelers alike. Each ruin bar is a canvas, constantly evolving through the contributions of local artists and patrons.

The Popularity of These Bars Among Locals and Tourists

Though they started as underground hangouts, ruin bars have become one of Budapest’s biggest cultural exports. Their unpolished charm and experimental energy have attracted both locals looking for alternative spaces and tourists seeking a uniquely Budapest experience. They are not just places to drink, they’re venues for art shows, film screenings, live music, and even farmers’ markets. Their popularity speaks to their versatility and the way they reflect the city’s raw creativity and resilience.

The Most Famous Ruin Bars

Among the many ruin bars scattered throughout the Jewish Quarter, Szimpla Kert stands out as both the pioneer and the poster child of the movement. Opened in 2002 in a dilapidated building on Kazinczy Street, Szimpla set the tone for what a ruin bar could be: a quirky, multicultural space filled with mismatched furniture, vintage TVs, bathtub seating, old bicycles hanging from ceilings, and a jungle of plants sprouting from every corner. Beyond its eccentric aesthetic, Szimpla Kert functions as a creative and social hub. It hosts live music, art installations, documentary screenings, and even a Sunday farmer’s market—transforming what could be just a bar into a community space that locals and travelers return to again and again.

Instant and Fogasház, which later merged into one massive nightlife venue, take the ruin bar experience in a different direction. Located in a vast complex just a few blocks away, this hybrid space offers an energetic, club-like atmosphere spread across multiple rooms and dance floors. While Szimpla leans into the artsy and laid-back vibe, Instant–Fogasház is where electronic music lovers, partygoers, and night owls gather to dance until dawn. The surreal decor, animal-headed sculptures, neon lights, and trippy wall art, enhances the dreamlike ambiance. Other noteworthy ruin bars include Mazel Tov, a more polished take on the concept with Middle Eastern cuisine and fairy-lit gardens, and Ellátó Kert, known for its colorful murals and relaxed courtyard. Together, these venues reflect the diversity within the ruin bar scene, offering something for every mood—from bohemian chill to full-on rave.

Comments are closed.